On the other side of the planet, India is also trying to promote a local alternative to Twitter called Koo. This happened after the Silicon Valley company didn’t comply with a government order and restored a few accounts — including publications, activists, and actors — after blocking them briefly. Authorities later criticized the social network’s actions and even threatened with penal actions. As the world moves towards the Splinternet, India’s trying to define its own versions through local laws and promoting homegrown apps. In this story, we’ll take a look at Twitter’s fight with India’s government, Koo’s opportunity to take advantage of that, and what challenges it could face by trying to rely on its nationalistic ties.

Twitter and India

Despite being a smaller social network than the likes of Facebook, Instagram, or TikTok, Twitter has always generated a lot of conversation globally, thanks to high-profile personalities posting announcements and breaking news on the platform, from world leaders to business bigwigs. The platform has been proactive in taking action against users violating its terms of service in the US — at least for the past year or so. But its actions in India have often been slow and culturally out of context. India is an important market for the social networking platform, with more than 17 million monthly active users. Twitter has had its controversial moments in the past in India. In 2018, when CEO Jack Dorsey visited India, he held up a poster — that addressed a controversial issue of castes — that some Indians found offensive. The company later had to apologize for it. In 2019, ahead of the country’s national elections, a bunch of Indian government officials alleged that Twitter was biased against conservatives and suppressed accounts with a right-wing slant. They also sent a summons to Dorsey to appear in front of a committee to get his views on “safeguarding citizens’ rights on social/online news media platforms.” Dorsey did not attend. Twitter’s latest spat comes at a time when India is trying to push local alternatives to global platforms. Plus, the company’s moderation decisions have given the government the perfect reason to promote a more nationalistic platform.

What’s Koo?

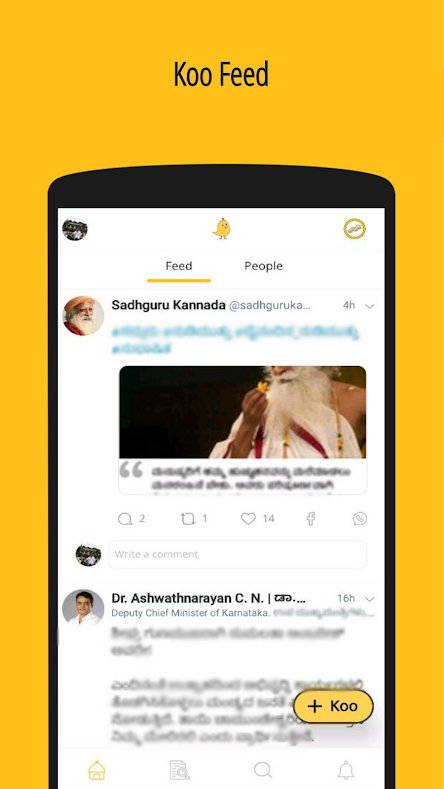

The app was the winner of the government’sAtmanirbhar’ (‘self-reliant’ in Hindi) challenge that challenged local developers to make world-class apps. As a result, the new social network is now being promoted by various government authorities. The app works pretty much like Twitter. You have your timeline, people to follow, and posts (Koos?). You can post text, GIFs, images, and videos, just like you would on Twitter. Users’ profile pages users and the rest of the app’s interface are also pretty similar, save for a different color scheme.

Moving to a new platform

It’s not only right-leaning people who’ve attempted to shift platforms. In 2019, Twitter restricted or blocked accounts of activists from minority castes. This sparked outrage amongst users and they started to leave the platform, and urged others to boycott the social network and join rival Mastodon. However, most users returned to Twitter, and Mastodon’s glory was short-lived. Previously, platforms like Tooter have loosely tried to create a ‘Desi Twitter,’ but failed to gain any traction. Now, Koo, which has seasoned founders, funding, and government support is trying to gain ground in the Indian market.

Koo’s opportunities

While Koo is currently a Twitter look-alike, government support and local language creators could boost the platform and help it gain traction across India. One of the main differentiators is that you can choose to see posts in a single language. That’s important in the Indian market, because people living in smaller cities and towns are more likely to engage with content in their local language. In 2019, Google sailed that nine out of 10 new internet users in India consume content in vernacular languages. ShareChat has also implemented this model, and it has more than 160 million users. The social network uses a Reddit-like model where users can take a look at content in different languages without logging in, and a lot of times, it doesn’t matter who’s posting the content. On the other hand, Koo’s Twitter-like framework could help people to connect with local leaders and influencers. Another important opportunity is political conversation and announcements. During its fight with Twitter, India’s IT ministry chose to post its response on Koo before sharing it on Twitter. If national and state ministries start posting on Koo first, it will make the platform an important hub for official information, forcing journalists and citizens to engage with it frequently. According to a report by Times Now, the government plans to begin posting its announcements first on Koo, and a few hours later on Twitter.

Is Koo’s shortcoming its biggest opportunity?

Currently, it doesn’t have an extensive privacy policy or community guidelines. And this could lead to the proliferation of toxic and hateful posts. While the company’s co-founder, Aprameya Radhakrishna, said in an interview that Koo doesn’t lean left or right on the political spectrum, the platform is currently filled with nationalistic posts. Despite presenting a neutral stance, last month, the app joined Aatmanirbhar Bharat Initiative, a nationalistic alliance started by Republic TV, a popular right-wing news channel. The app is already facing issues in terms of controlling hate speech. A report by BuzzFeed News noted that there are a ton of posts on the social network that express hatred towards Muslims. Meanwhile, Radhakrishna says it’s hard to moderate every post on the platform. In a conversation with Rest of World, he emphasized that it doesn’t want to take editorial control of its content like Twitter: This could create a difficult pipeline for the platform as it has to wait for an official order to remove something from the platform instead of taking action. Its reactive approach might not be the best strategy if the intention is to provide a safe environment for users to interact in. Koo also offers a feature that lets you edit posts — something Twitter users have been demanding for a long time. However, there’s no indicator to mark an edited post or display the changes made to a post. This could lead to people altering their posts after the fact to escape the consequences of what they’ve shared on Koo.

Koo’s co-existence with Twitter

India presently has more than 600 million internet users — that’s less than half of its population. American companies such as Twitter and Facebook have captured the majority of the local English-speaking population in the country. However, Indian companies such as ShareChat and DailyHunt have relied on local languages to gain userbase. Last year’s Chinese app bans that saw TikTok and PUBG being blocked in India, have accelerated platforms and games such as Mitron, Moj, and FAU-G. Koo is currently relying on support from the government to gain momentum. India’s new social media rules and backing from various authorities mean that the app can wait for government orders for moderation rather than actively building community guidelines. In contrast, Twitter has stronger community guidelines and it’s even called censor of free speech by various world leaders such as Germany’s Angela Merkel and UK’s Boris Johnson. While Koo might not directly replace Twitter, become home to nationalistic voices, where there’s no fear of being censored.